- This topic is empty.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

June 25, 2025 at 3:15 am #10103

Kris Marker

KeymasterWe post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

‘DON’T THINK ABOUT THE BIG WHITE BEAR’ IN SENTENCING SUPERVISED RELEASE VIOLATIONS, SCOTUS TELLS JUDGES

When a federal prisoner who is out of prison but serving a term of supervised release (a version of parole after a prison term is served) gets violated for breaching one of the many supervised release conditions, the Court may impose some more time in prison. When doing so, the supervised release statute (18 USC § 3583(e)) directs the Court to consider most of the sentencing factors in the Guidelines.

When a federal prisoner who is out of prison but serving a term of supervised release (a version of parole after a prison term is served) gets violated for breaching one of the many supervised release conditions, the Court may impose some more time in prison. When doing so, the supervised release statute (18 USC § 3583(e)) directs the Court to consider most of the sentencing factors in the Guidelines.But not all. Conspicuously missing from the list of permissible factors listed in § 3583(e) is § 3553(a)(2)(A), which directs a district court to consider “the need for the sentence imposed… to reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense.”

Edgardo Esteras pled guilty to conspiring to distribute heroin. The district court sentenced him to 12 months in prison followed by a 6-year term of supervised release. He did his time and began his supervised release. Eventually, he was arrested and charged with domestic violence and other crimes.

The district court revoked Eddie’s supervised release and ordered 24 months of reimprisonment, explaining that his earlier sentence had been “rather lenient” and that his revocation sentence must “promote respect for the law,” a consideration enumerated in 18 USC § 3553(a)(2)(A) but not authorized to be considered in fashioning a supervised release revocation sentence by § 3583(e).

The 6th Circuit affirmed the sentence, holding that a district court may consider § 3553(a)(2)(A) when revoking supervised release even though it is not one of the listed factors to be considered in 18 USC § 3583(e).

Legend has it that as a boy, Russian author Leo Tolstoy and his brother formed a club. To be initiated, the aspirant was required to stand in a corner for five minutes and not think about a big white bear. Last week, the Supreme Court told district courts to ignore the bear when sentencing supervised release violations.

Legend has it that as a boy, Russian author Leo Tolstoy and his brother formed a club. To be initiated, the aspirant was required to stand in a corner for five minutes and not think about a big white bear. Last week, the Supreme Court told district courts to ignore the bear when sentencing supervised release violations.Writing for the 7-2- majority, Justice Barrett reversed the 6th Circuit in what seemed to be an easy lift for the Court. The decision applied the well-established canon of statutory interpretation “expressio unius est exclusio alterius” (expressing one item of an associated group excludes another item not mentioned). In other words, where a statute provides a list of what can or cannot be considered – the classic example being Section 61 of the Internal Revenue Code, which lists ten examples of what constitutes “gross income” – that detailed list implicitly excludes anything not listed.

Likewise, the Supreme Court held that where Congress provided in § 3583(e) that the Court should consider a list of eight of the ten sentencing factors from 18 USC § 3553(a) when sentencing on a supervised release violation, “[t]he natural implication is that Congress did not intend courts to consider the other two factors…” Justice Barrett wrote that “Congress’s decision to enumerate most of the sentencing factors while omitting § 3553(a)(2)(A) raises a strong inference that courts may not consider that factor when deciding whether to revoke a term of supervised release. This inference is consistent with both the statutory structure and the role that supervised release plays in the sentencing process.”

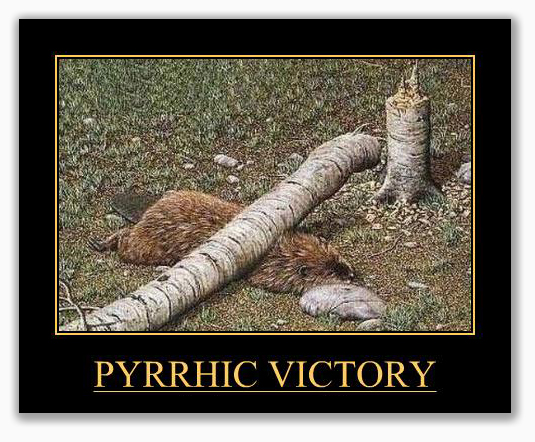

But such a Pyrrhic victory! Any judge worth a robe and wig can easily figure out how to throttle a mutt like Eddie — who unquestionably got a real break in his original heroin sentence — with a maxxed out supervised release sentence that will withstand judicial review. The supervised release sentence may still be based on the “nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant” (§ 3553(a)(1)), on the need “to afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct” (§ 3553(a)(2)(B)) and the need “to protect the public from further crimes of the defendant” (§ 3553((a)(2)(C)). The judge can describe the offender as having the characteristic of “not learning from his mistakes” or as needing a long supervised release sentence because he has not yet been deterred from criminal conduct or as needing to be locked up to protect the public.

But such a Pyrrhic victory! Any judge worth a robe and wig can easily figure out how to throttle a mutt like Eddie — who unquestionably got a real break in his original heroin sentence — with a maxxed out supervised release sentence that will withstand judicial review. The supervised release sentence may still be based on the “nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant” (§ 3553(a)(1)), on the need “to afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct” (§ 3553(a)(2)(B)) and the need “to protect the public from further crimes of the defendant” (§ 3553((a)(2)(C)). The judge can describe the offender as having the characteristic of “not learning from his mistakes” or as needing a long supervised release sentence because he has not yet been deterred from criminal conduct or as needing to be locked up to protect the public.Different spirits summoned, but the same result. As long as no one mentions the big white bear, a canny sentencing judge can think about the bruin all he or she wants to and sentence accordingly.

As for Eddie, he finished his supervised release sentence in October 2024, so the Supreme Court decision does little for him. But maybe it will have some beneficial effect. It seems Edgardo was arrested on a fresh supervised release violation last month and is currently held by the Marshal Service. He will appear in front of Judge Benita Y. Pearson (N.D. Ohio) for a hearing in three weeks.

We’ll see if the bear comes up during that hearing.

Esteras v. United States, Case No. 23-7483, 2025 U.S. LEXIS 2382 (Jun 20, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.