- This topic is empty.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

January 27, 2026 at 3:13 am #11355

Kris Marker

KeymasterPolice misconduct is notoriously difficult to track, penalize, and prevent, a problem that advocates have increasingly focused on in the years since the murder of George Floyd. In the time since we published a list of policing resources in 2020, advocates and researchers have been working to collect, analyze, and publish data from public records produced by various state and local law enforcement agencies.1 Particularly in the wake of more recent nationally-galvanizing killings, this time at the hands of federal ICE agents, these projects offer a blueprint for community members to track and advance law enforcement accountability. We “spotlight” some of these resources here for anyone interested in digging deeper into questions related to police accountability, especially through public records, because we think they offer compelling information and models that can be used or replicated by others. This is by no means an exhaustive list of resources related to police misconduct; several other groups have compiled far more comprehensive lists of available data sources.

Data sources that focus on misconduct incidents and patterns instead of officers

The projects we spotlight in this briefing focus on the actions of specific law enforcement officers and agencies, but other projects offer data on incidents and victims of police violence.

The projects we spotlight in this briefing focus on the actions of specific law enforcement officers and agencies, but other projects offer data on incidents and victims of police violence. Mapping Police Violence has the most comprehensive database of killings by law enforcement in the United States, dating back to 2013 and categorized by race, type of force used, geography, agency, and more. They also publish data visualizations that help advocates communicate the gravity and severity of police violence. Fatal Encounters maintains similar data from 2000 to 2021 and formed the basis of the National Officer-Involved Homicide Database, created in 2022 and publicly accessible with a data use agreement. The Center for Policing Equity works with law enforcement agencies willing to share their data to assess racial equity in local policies and practices; as of this publication, only 13 communities’ assessments have been made public, but they demonstrate the potential of robust data collection and analysis. The Center also offers detailed guidance for communities that want to improve local policing data. Open Data Policing makes stop, search, and use of force data publicly available; the database covers all known traffic stops in North Carolina since 2002, Illinois since 2005, and Maryland since 2013 and also includes officer information. This is inevitably an inexhaustive list of resources, but includes the largest databases we are currently aware of.

These efforts are particularly essential at a time when the federal government is actively eliminating its own initiatives to enhance police accountability (and even suppressing and mischaracterizing evidence). Last year, for example, the Trump administration deleted the National Law Enforcement Accountability Database, which tracked misconduct among federal law enforcement, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and federal Bureau of Prisons employees.2

Of course, some cities maintain their own “open data” databases and dashboards (like these), with many more coming online since 2020. But in less populous jurisdictions and those that lack the resources or political will to prioritize police transparency, misconduct continues to be swept under the rug and under-investigated; this is where projects like these come in.

Police misconduct databases

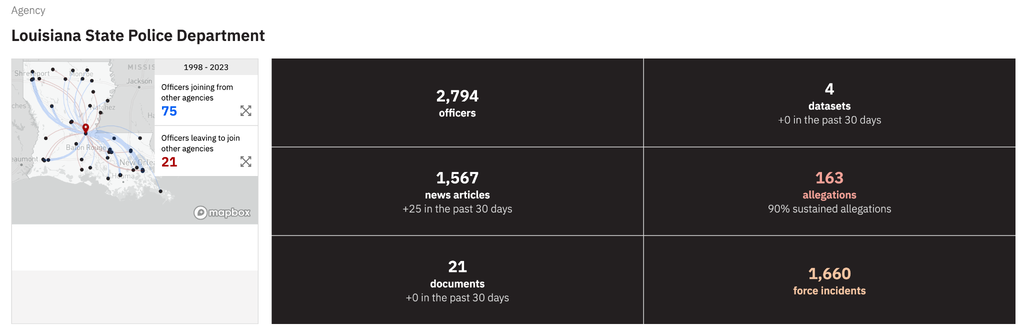

The Louisiana Law Enforcement Accountability Database

The Louisiana Law Enforcement Accountability Database (LLEAD) consolidates data from over 600 law enforcement agencies across Louisiana. The searchable and downloadable LLEAD database includes employment history data, police misconduct records, use of force reports, certifications and qualifications, and other data like salary (when available) and settlement payments. All the data is public information collected from police departments, sheriffs’ offices, civil service commissions, fire and police civil service boards, and courts, typically collected through public records requests.

The LLEAD database was initially designed to help Innocence and Justice Louisiana (formerly Innocence Project New Orleans) identify potential cases of wrongful conviction and aid in litigation for their clients, as well as to help identify statewide policing trends. Today, the database is a tool to push for increased law enforcement accountability and transparency across the state, including pressuring the Council on Peace Office Standards and Training (POST) for more transparency on officer employment. The available data can also be used to investigate use of force and misconduct trends across Louisiana agencies, as well as trends in appeals and settlements across jurisdictions.

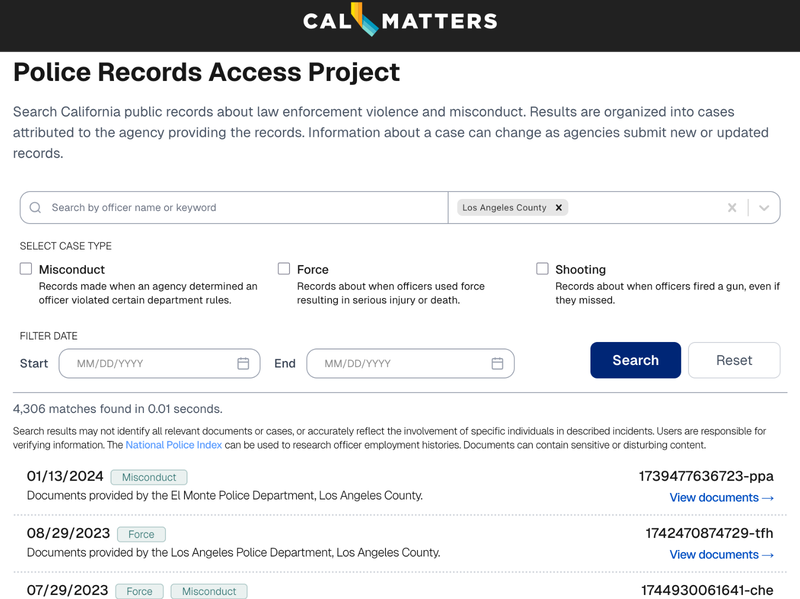

The California Police Records Access Project

The Police Records Access Project (PRAP), created by the Community Law Enforcement Accountability Network (CLEAN), contains public records from nearly 700 law enforcement agencies across California, including police and sheriffs’ departments, public school and university police forces, prisons, probation departments, district attorneys, coroners, medical examiners, and other government agencies. Prompted by California’s 2018 “Right to Know” Act, which gave the public access to records related to police shootings, use of force, and certain kinds of misconduct, the CLEAN coalition of investigative reporters and data scientists built out this database with thousands of public records. To organize the mountain of information by date and type of case, the team behind PRAP uses generative AI, but they stress that “these uses of GenAI do not directly impact the information that is shown to users,” and searches only return “documents with a literal match to the search term(s) in the source text.” The tool is user-friendly and searchable by officer name, agency name, county, case type (misconduct, force, or shooting) and date.

The extent of the historical data in the PRAP database varies between agencies, but often stretches back decades. For example, there are documents available about Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office shootings as early as 1977. Beyond researchers and journalists, the database also offers public defenders and attorneys easy access to relevant public information about arresting officer(s) in recent cases.

Illinois Open Police Data

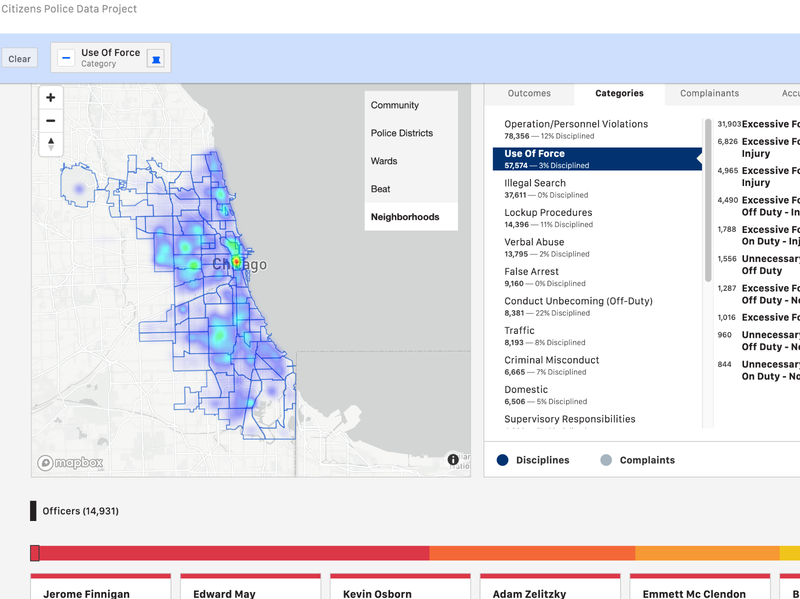

The story of the Invisible Institute’s Civic Police Data Project (CPDP) began almost two decades ago, when journalists filed a lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department forcing the city to release complaint records that ultimately became public information in 2014. The database, which is specific to Chicago, includes (among other things) officer demographics and identifying information, unit information, data on misconduct and outcomes (disciplinary actions and legal settlements), employment history, and a map of complaints, sustained allegations, and use of force reports spanning from 1988 to 2018.

The project also includes community-level information. The database breaks down allegations, officers with complaints, and complaint-level data by community, neighborhood, police district, ward, and police beat. It also includes aggregated demographic data for complainants as well as for accused officers, so, for example, users can see where complaints come disproportionately from Black residents or women. The entire dataset can be downloaded, and the CPDP data tool makes it easy to search and filter using names, places, outcomes, complaint categories, and time periods.

In a remarkable example of how this dataset (and others) can be used, the Invisible Institute created the Beneath the Surface project, which investigates gender-based police violence against Black women and girls. Project contributors have used the Chicago data to identify patterns in complaints indicating (among other things) misconduct in missing persons cases, officers ignoring and/or mistreating sexual assault survivors, and the failure of Internal Affairs to adequately investigate misconduct in sexual assault cases.

The Invisible Institute is now expanding upon its work from Chicago’s Civic Police Data Project to look into police misconduct in other cities and counties in Illinois. To date, they have created a database from Champaign-Urbana data and are in earlier stages in Rockford, Joliet, and Will County.

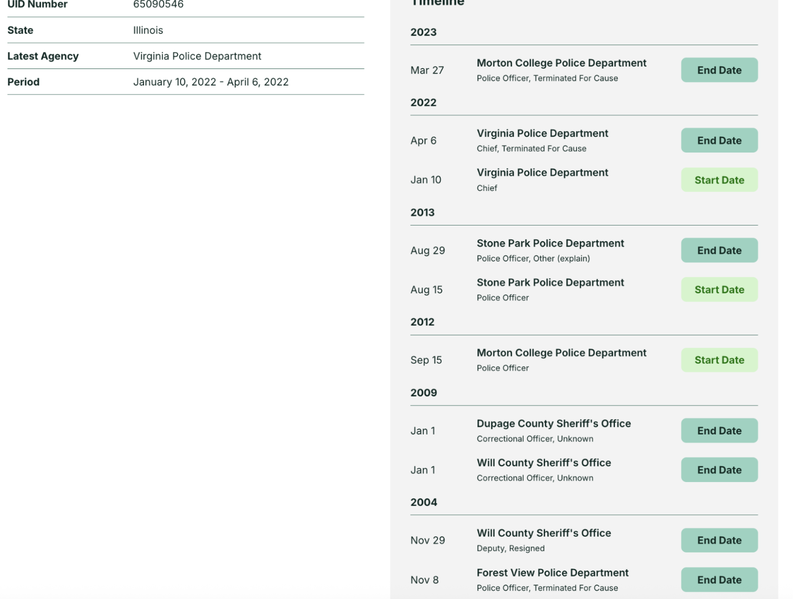

The National Police Index: Officer employment history

The National Police Index (NPI) is the largest of the projects we highlight here in terms of geographic coverage, but also has a narrower scope than the others as it is focused mainly on law enforcement employment history. The NPI tool is intended to help identify potential “wandering officers” — that is, officers fired from one department, sometimes for serious misconduct, who then find work at another agency, often leading to a pattern of short stints at multiple agencies across the state or country. Populated by a coalition of news and legal organizations across the country, the data tool offers employment histories for police officers in 24 states and counting.3 Individual-level data include the officer’s current agency and most recent start date, as well as a dated timeline of previous law enforcement positions. While the database does not include many details about disciplinary action, Florida and Georgia also provide information detailing terminations or resignations following department-requested investigations.

The Human Rights Data Analysis Group and other projects they support

All of the projects highlighted so far have been facilitated in one way or another by the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG) and its Data Scientist, Tarak Shah. HRDAG has also supported projects in other jurisdictions that use public records to investigate law enforcement actions. For example, the ACLU of Massachusetts produced a data tool on Boston Police Department SWAT Raids from 2012 to 2020 that includes the number of raids per year, raid locations, raid details, office use of force, and demographics of people targeted by raids. HRDAG also supports Kilometro Cero, a nonprofit organization in Puerto Rico that tracks police use of force documented in official Police Bureau reports and publishes their analyses on their website.

Further, while not a new data collection project, in 2015 two researchers from HRDAG applied findings from studies of unreported killings in other countries to estimate how many homicides committed by police go unreported in the U.S. They concluded that the number reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (which already supplemented official reports with media reports) excludes nearly 30% of police killings, suggesting that more data collection and documentation (i.e., from nongovernmental sources) is needed to accurately gauge the scale of deadly police violence.

Other noteworthy police accountability data projects

This briefing spotlights just a few projects that illustrate how public records can be used to investigate and track police misconduct, discipline, and employment, and in turn, how these projects can put pressure on law enforcement agencies to improve their practices and decisions. Many other projects use similar methods for the same purposes, and are worth exploring further, such as:

- The Chicago Justice Project’s Police Board Information Center compiles, archives, and analyzes Chicago Police Board documents related to allegations of serious misconduct, which it obtains through public records requests. Along with archiving case details, the site tallies the number of cases related to specific rules of conduct, trends in case outcomes, and individual Board member recommendations by case.

- The New York City Legal Aid Society’s Cop Accountability Project (CAP) offers the city’s most comprehensive public database of law enforcement misconduct records, containing over 500,000 records: The Law Enforcement Look Up (LELU). The LELU includes officer demographic and employment information, number of complaints and substantiated complaints, and much more. The project has been used in lawsuits against the NYPD, including a lawsuit regarding brutal policing tactics during the protests in 2020, as well as in detailed analyses of patterns of police enforcement in New York.

- In Philadelphia, the Police Transparency Project’s Unconstitutional Pattern and Practice Database is designed for use by attorneys to share information from court documents about police misconduct, particularly for the purpose of identifying and overturning wrongful convictions.

- The ACLU of Vermont has published a database of “Brady letters” gathered through public records requests. As the organization explains, “when Brady-related issues arise — like an officer exhibiting bias or getting caught lying — state’s attorneys generally send a ‘Brady letter’ to their county’s criminal defense attorneys noting that the officer has known credibility issues. This information may then be raised by defense counsel to call into question the reliability of the officer involved in the case.”

- Journalists at Behind the Badge are using public records to make a comprehensive database of police misconduct across New York State’s 500-plus law enforcement agencies. As of 2024, they had obtained files from 290 of those agencies. Their strategy involves requesting records provided to district attorneys’ offices by law enforcement as part of “Brady” disclosure obligations.

- OpenOversight, a project of Lucy Parsons Labs, is a volunteer-run searchable database of law enforcement officers, including photos and other details wherever possible. Currently, the site offers data from 24 departments across five states, but active projects based on this model have also been developed in Seattle and Virginia.

Building upon this work

For readers interested in starting new projects focused on documenting law enforcement actions, the examples highlighted in this briefing can serve as roadmaps. Additionally, a few organizations offer very detailed “how to” guidance. The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ Full Disclosure Project offers an excellent guide to getting started tracking police misconduct including tips for effective public records requests, a list of police misconduct data sources to look for, and more. And building off of 30 years of experience, Berkeley Copwatch and WITNESS have created extensive resources from the People’s Database for Community-based Police Accountability, including a planning workbook, sample data models, a database template, and data dictionary. (WITNESS also provides a broader range of resources on filming protests, police misconduct, immigration enforcement, and documenting during internet shutdowns, among other topics.)

Conclusion

Law enforcement officers violate laws and policies designed to protect the public all the time, but very rarely are they held accountable for their actions. This is what makes these data projects so important: when formal accountability mechanisms fail, it’s up to the public to document and distribute evidence of violence and misconduct. Doing so can create pressure for change and educate others about the size and scope of the problem. Collaborative research efforts to compile public law enforcement records into user-friendly databases, like those highlighted in this briefing, exemplify the power of data and analysis to aid in advocacy. They help empower journalists, attorneys, advocates, and the broader public to hold law enforcement accountable when they engage in misconduct. And ultimately, greater transparency helps combat impunity and reduce the harm these systems perpetuate.

Footnotes

-

In addition, local and state governments have also taken steps to track and address police misconduct: from 2020 to 2022, at least 48 states enacted at least one police accountability policy, most commonly focused on training and technology requirements. For a detailed review of police accountability policies and legislation passed between 2020 and 2022, see State-by-State Review: The Spread of Law Enforcement Accountability Policies (2025). ↩

-

The National Decertification Index, a national registry of certificate and license revocation actions related to police misconduct, still exists but is only accessible to law enforcement agencies to guide hiring decisions. ↩

-

As of this publication date, the National Police Index has full data from 24 states and more limited data from one other state. The website mentions it has data coming soon for four more states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. ↩

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.