- This topic is empty.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

February 3, 2026 at 3:13 am #11396

Kris Marker

KeymasterOver the past 35 years, specialty courts — also called diversion courts, treatment courts, or problem-solving courts — have exploded in popularity.1 The first specialty courts, drug treatment courts, came about when judges began facing overwhelming drug caseloads from the “war on drugs.” The idea behind them was that people with substance use disorders facing criminal charges could obtain treatment and avoid rapidly overcrowding jails and prisons, so long as they complied with all conditions ordered by a judge. This subtle shift away from punishment and toward so-called “therapeutic” measures took the criminal legal system by storm, becoming a model for other courts. Today, there are over 4,200 specialty courts in operation, with one in nearly every state.2

Slideshow 1. The number of specialty courts has grown almost every year since their inception. Swipe for a detailed view of specialty court growth since 2009.

Proponents claim that specialty courts are tackling social issues, reducing crime, and saving taxpayer money through fewer days (or years) of costly incarceration.3 Evaluations suggest that some people have turned their lives around by completing specialty court programs, and public opinion toward them is generally very positive, recognizing their rehabilitative potential. The model sounds ideal, and appears to move away from harsh carceral responses to social issues while connecting people with treatment and support.

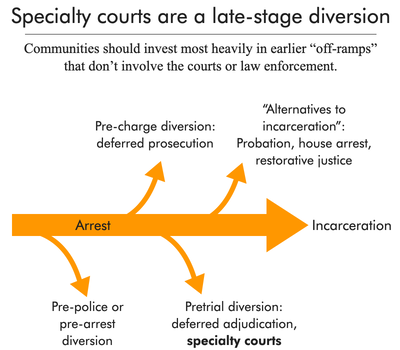

Figure 1. See our diversion report for more information.

But specialty courts may be receiving more attention and investment than their lukewarm success actually calls for. In reality, attaching treatment opportunities to a traditional court system and the threat of jail time actually expands the punishment system while undermining other community-based public safety solutions. Below, we offer a brief overview of specialty courts and outline six ways that they miss the mark on effectively diverting people from incarceration and providing pathways to long-term health and stability.

- Specialty courts have had mixed success in improving public safety or public health

- Overly narrow criteria place specialty court programs out of reach for many

- Outdated public health principles persist in specialty courts

- Specialty courts don’t shrink the footprint of mass incarceration — and may in fact enlarge it

- Judges lean too heavily on jail as a response to noncompliance, negating treatment progress

- The team-oriented approach reveals personal and clinical information to judges, leading to undue scrutiny and punishment

The national landscape of specialty courts

Adult drug courts were the first type of specialty court, and have long been the most common, currently making up about 44% of all specialty courts.4 Other major categories are aimed at mental health, veterans, family treatment (for parents of minor children who have both substance use issues and active child welfare cases), and domestic violence.5 Given that specialty courts try to address underlying factors, most center or deal with substance use in some way; some of these courts are specifically aimed at youth, people who have opioid use disorders or co-occurring disorders, who are part of tribal populations,6 or who face charges for driving while impaired (DWI).

Well over 100,000 people go through specialty courts each year,7 although not all participants “graduate.”8 In their most recent (2022) census of specialty courts, the National Treatment Court Resource Center published national participation data for each major type of court:

How many people go through specialty courts each year?

Table 1. Participation in specialty courts across the U.S. in 2022, by type of court, from the National Treatment Court Resource Center’s Painting the Current Picture census. Kansas, Massachusetts, South Carolina, and Virginia provided the number of operational courts by type, but did not provide participation data. Court type Number of operational programs Number of states/territories with programs Number of participants Adult drug court 1,833 50 77,811 DUI/DWI 320 33 11,288 Family treatment court 374 35 6,458 Mental health court 618 36 15,038 Veterans’ treatment court 537 41 7,737 Juvenile drug treatment 265 31 2,925 Total 3,947 121,257 As the table suggests, all 50 states had an adult drug court in 2022; Connecticut has since shuttered its last few drug courts. It’s unclear why the state did away with them, and state specialty court coordinators could not be reached to provide more information. In the future, Connecticut may serve as a case study on what a state criminal legal system looks like without specialty courts.

Six problems with specialty courts

1. Specialty courts have had mixed success in improving public safety or public health

More research has been published about specialty courts (specifically, drug courts) than virtually all other criminal legal system programs, combined. This fact might suggest that specialty courts come with robust evidence of their success, but outcomes — such as changes in incarceration, crime, or drug use — vary widely by court. A closer look at individual program evaluations, as well as larger meta-analyses, reveals that specialty courts do just “okay” at achieving their purported outcomes. And while some courts show short-term improvements in public safety or public health measures, longer-term outcomes (after about three years) appear to be no different for specialty court participants than for people in the traditional court system.

The evidence, some of which we’ve collected below, should be a warning to lawmakers that the deep investments in specialty courts are not yielding the results that proponents claim or hope to achieve:9

- Fewer participants in a Baltimore, Md. drug court were re-arrested than non-participants for two years, but this positive outcome became insignificant after three years. Furthermore, during the three-year follow up period, participants spent approximately the same amount of time incarcerated as did people in the control group as a result of the initial arrest.10

- In Maricopa County, Ariz., drug court participants showed no reduction in recidivism or drug use after 12 months; a 36-month follow-up study went on to show no difference in the average number of arrests between participants and a control group.

- A review of three mental health courts with similar characteristics found no change in arrests or jail time for court participants compared to a control group.

- A 2022 review of Maryland’s “adult treatment courts” found no changes in arrest rates among participants: Two years after program entry, 46% of participants had been rearrested compared to 45% of the control group. The review’s author argues that participants are being rearrested fewer times than non-participants, but the difference (1.3 versus 1.5 average rearrests over two years) is negligible and not statistically significant.

- Participants in an “opioid intervention court” were less likely to die in the 12 months following their jail booking, but researchers noted that anyone receiving mediation-assisted treatment within 14 days of their booking was less likely to die, regardless of court participation. Emergency department visits and overdose-related deaths fell in the region surrounding the opioid court after its implementation, but it’s unclear how or whether this change can be attributed to the court. Meanwhile, arrests of court participants were much higher than they were for “business as usual” defendants.11

These underwhelming findings persist even though specialty court participants are sometimes “cherry-picked” for their likelihood to do well. And presumably, those who complete specialty courts will indeed be less likely to be rearrested or use substances for which they were treated than those who don’t finish, but graduation rates around 50% are not uncommon.

Slideshow 2. Swipe to see examples of specialty court completion and failure rates. Sources for slide 2: Judicial Branch of New Mexico, New Mexico Treatment Courts Report FY2022; NPC Research, Vermont Statewide Treatment Court Outcome Cost & Evaluation, Summary of Key Findings, December 2023; National Center for State Courts, Michigan’s Adult Drug Courts Recidivism Analysis, May 2017.

2. Overly narrow criteria place specialty court programs out of reach for many

Like many other criminal legal system reforms, specialty courts are often designed in a way that includes certain people or criminal charges, and excludes others — a reality known as carveouts. Studies and experts suggest that specialty courts work best when serving high-risk or high-need individuals, even though many courts still exclude people with violent or serious charges, those with a criminal history,12 or those with greater health needs. For example, a 2013 meta-analysis found that 88% of U.S. drug courts excluded anyone with a prior violent conviction and 63% excluded those with a current violent charge. Some specialty courts are even more specific, excluding people facing firearm or drug trafficking charges.13

Ultimately, even when someone meets all eligibility criteria, they may still be excluded from specialty courts because a prosecutor or judge must choose to offer the option.14 This discretion can work to include some people and to exclude others: Many advocates and skeptics argue that participants are “cherry-picked” or low-risk cases are “skimmed” in order to ensure success. One study, though limited in scope, found that one-third of a cohort of drug court participants did not actually have a clinically significant substance use disorder, suggesting that program spots are not appropriately prioritized.

Furthermore, discretion can lead to racial disparities in specialty court enrollment; research has shown that Black and Latinx people are offered diversion less often than white people, even after controlling for legal circumstances. Charge-based carveouts can just as easily lead to these disparities, given the overwhelming evidence that Black defendants face more — and more severe — charges for the same crimes. It’s difficult to pin down which is the most insidious factor in excluding racial and ethnic minorities, but specialty courts will inevitably fail to make an impact under such exclusionary rules.

3. Outdated public health principles persist in specialty courts

Many specialty courts adhere to woefully outdated ideologies about treatment and accountability instead of using evidence-based public health practices. Specifically, rigid attitudes toward drug use have kept these courts from embracing “what works” for long-term recovery:

Abstinence. The abstinence model of addiction treatment, in which people are punished for failing to completely stop their drug use, runs counter to the reality of substance use disorders as experienced by many specialty court participants. Abstinence also may not align with drug users’ objectives, which may look more like reduced drug use or improved quality of life in other areas. So-called “best practices” for adult drug courts require abstinence in order to advance through their program and graduate. Abstinence may work for some people, but it’s highly controversial (compared to non-abstinence or harm reduction techniques) because of its oversimplified and often unrealistic approach to substance use.15

Stigma against medication-assisted treatment. Similarly, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) — which should be widely available in all community-based and carceral treatment settings — is not available in all specialty courts. A 2012 survey of drug courts found that most participants were opioid-addicted, but only half were actually offered agonist medication (such as methadone or buprenorphine); additionally, half of programs had blanket prohibitions on some of these medications. And because MAT requires, as the name suggests, the use of medications that have been shown to effectively treat substance use disorders, abstinence-based specialty courts may prohibit MAT altogether. Some judges presiding over specialty courts, showing a personal preference for abstinence, do not look favorably on MAT, and court personnel may have mixed (though misguided) attitudes toward some MAT medications.

Mandatory treatment. Because specialty courts operate as an alternative to incarceration, participants are required to complete a treatment regimen or risk sanctions ranging from light warnings to jail time. But forced drug treatment is widely understood to be harmful, unethical, and ineffective. Instead, drug treatment should always be available to participants on a voluntary basis, and specialty courts can center other efforts, like securing housing or other medical care, as part of a broader harm reduction strategy to support those who continue using drugs.

4. Specialty courts don’t shrink the footprint of mass incarceration — and may in fact enlarge it

There are two major ways that specialty courts do not hold up their end of the bargain as true diversion programs: They do not prevent incarceration to the extent that they claim, and they can actually expand the number of people within the criminal legal system — a phenomenon known as “net-widening.”

Specialty courts have been so appealing to criminal legal system actors that they have been used as a justification for arresting greater numbers of people.16 Data from Denver, Colo., for instance, shows an unmistakable rise in drug cases after a drug court was established there in 1994. In the words of a former drug court judge, “the very presence” of this court led to an influx of cases that law enforcement and judicial systems otherwise “would not have bothered with before.” And given the typically low graduation rates from specialty courts, this growth in cases means more people are being convicted and sentenced to prison or jail, which is antithetical to the intention behind them — and is hardly saving taxpayer money.

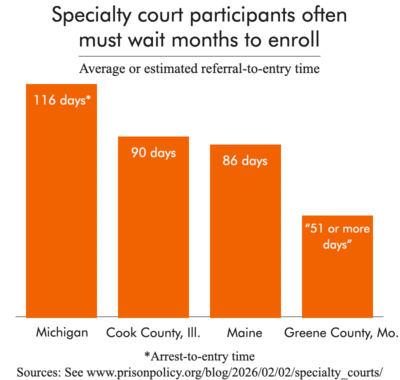

As for those who are selected for specialty court programs, jail incarceration and long wait times are often disappointingly essential to the enrollment process. This length of time can vary widely and is seldom tracked, but some resources suggest a maximum time of 50 days from arrest to program entry (let alone referral to entry). In Maine’s specialty courts, wait times since have long exceeded the 50-day suggestion; we also found arrest-to-referral or referral-to-entry times ranging from a vague “51 or more days” in a Missouri county drug court to an appalling 116 days in Michigan’s drug courts. Meanwhile, participant interviewees in Cook County, Ill. specialty courts talked about being “often incarcerated” during screening processes, with court official interviewees affirming that jail time in this context might last from three to four months.

Figure 2. In some cases, people wait behind bars for a spot to open up.

Finally, most specialty courts — about two-thirds, according to a 2012 census — require participants to plead guilty before enrolling, saddling them with a criminal record just to access treatment. This post-plea model can make participants ineligible for similar opportunities in the future. Graduates of specialty courts may be able to have their criminal conviction vacated or their record expunged, but again, dismal graduation rates and barriers to record clearing mean that many thousands of people have only been punished by this purported “alternative” to punishment.

5. Judges lean too heavily on jail as a response to noncompliance, negating treatment progress

Although specialty court proponents espouse the benefits of team-oriented, less-formal approaches that encourage “graduated” sanctions beginning at light verbal warnings, people who are simply not able to meet program requirements will likely be brought to jail eventually. Jail is not a helpful place for people who are struggling with the very problems that specialty courts claim to address: Isolated and violent environments can cause lasting damage to mental health, and mental health and drug treatment are limited if they exist at all. Meanwhile, though corrections officials are reluctant to admit it, drugs are prevalent behind bars, creating the ultimate foil for anyone seeking help curbing drug use.

Still, judges have the ability to send participants to jail if they find that program requirements aren’t being met — and they often do. Even when jail time is a short-term, last-resort sanction, a recent survey of over 400 courts found that most (72%) use jail sanctions “at least some of the time” for positive drug tests.17 Jail sanctions from a specialty court can range from a few days to a couple of weeks; one study of Michigan’s drug courts found that the average jail sanction was 15 days. And as we’ve explained before, even short jail stays are harmful, disruptive to treatment and overall stability, and can even be deadly. Unsurprisingly, there is no evidence that jail incarceration actually “works” as part of a sanction system to encourage compliance with specialty courts.18

6. The team-oriented approach reveals personal and clinical information to judges, leading to undue scrutiny and punishment

Specialty courts typically have a presiding judge working alongside people such as social workers, prosecution and defense attorneys, court personnel, and probation officers to manage each participant’s case. Like other courts, specialty court judges have the final word, but they often consult with their teams and spend more time interacting directly with participants compared to traditional criminal courts. Proponents see this “holistic” approach to treatment and rehabilitation as supportive and humanizing for participants, but this process can also blur professional boundaries because it leads to closer scrutiny of individuals’ behavior compared to a traditional court. When judges have more access to participant’s lives and sensitive clinical information, they have more power to take action on that information.

A recent qualitative study of specialty court judges in Virginia affirms these same concerns (though they are not framed as such in the study, which was published in a pro-specialty court journal). Judges reported asking participants more personal questions than they would in a normal docket in order to establish a positive rapport, calling their role of neutral arbiter into question.19 They also revealed that in lieu of formal training, many simply followed their predecessor’s protocols in the courtroom. Judges enjoy specialty court roles because they feel impactful and rewarding compared to a strictly-punitive criminal court docket; this strong sentiment may explain why these courts have persisted for so long, and why they remain largely unregulated spaces.20

A multidisciplinary team of service providers and case managers is essential to addressing complex health needs, but including judges and law enforcement in the conversation will ultimately be counterproductive to those ends, and keep people cycling through jails.

Specialty courts should be a last-resort diversion opportunity for people facing criminal charges

On paper, specialty courts make sense as a policy tool with broad appeal, marrying treatment with traditional accountability and punishment. But in the rush to introduce treatment through courts in this way, communities haven’t often considered the question of whether the criminal legal system should be involved at all. Unfortunately, the underwhelming outcomes and systemic issues presented here have not yet been enough to shift the paradigm. One Massachusetts lawmaker who once championed the model recently explained how his attitude toward drug courts has changed (emphasis added):

After roughly 10 years of thinking about how courts could play a role in substance use recovery, I reached the conclusion that a partnership between the treatment system and the criminal justice system was a deeply problematic idea, as appealing as it seemed initially. I formed the view that, although there is a close relationship between addiction and crime, treatment of addictions should generally be a matter left to voluntary participation in the health care system.

While some lawmakers are waking up to the reality of specialty courts, for now this movement has broad bipartisan support and courts are still expanding in many states.21 Lawmakers should strongly consider implementing legislation that prioritizes “upstream” diversion opportunities and minimizes the drawbacks of specialty courts:

- Provide medication-assisted treatment (MAT) in any specialty court dealing with substance use disorder. Courts resist MAT due to misconceptions and stigma, but it is widely held as the gold standard treatment. Judges and court personnel should be thoroughly trained on how MAT works and why it’s effective.

- Get rid of charge-based or history-based exclusions. There is no evidence base for excluding certain people or charges from these programs, and carveouts are a moralizing choice that is actually counterproductive; research suggests that specialty courts are less effective for low-risk participants.

- Follow harm reduction principles. Harm reduction incorporates the most person-centered and health-centered practices while rejecting punitive measures. The Center for Court Innovation’s detailed guide on using a harm reduction lens is geared toward drug courts, but it can be used in any type of specialty court setting.

- Eliminate requirements that lead to a criminal record or jail time. People hoping or waiting to be referred to a specialty court should not have to plead guilty or languish behind bars for days or months. And jail should never be a punishment for relapse, as it disrupts treatment and leads to further instability.

- Center clinician roles and decisions, expand screenings for psychological disorders, and require thorough training for judges and court personnel. Judges go through little-to-no training before presiding over a specialty court, and go on to make decisions using participants’ sensitive health information. At the same time, screening protocols can be too brief to understand individual, complex health needs that may send someone down an inappropriate treatment path, setting them up for failure.

- Pass legislation that creates robust standards and oversight. Because of their rapid proliferation and popularity among judges, specialty courts are highly unregulated. Some states working on this include Wyoming and Illinois; in New York, the Treatment Court Expansion Act — supported by a large and diverse coalition of groups — would establish state-mandated, pre-plea mental health courts open to all functional impairments.

Ultimately, specialty courts should be a much smaller piece of the diversion landscape, and community-based interventions should be prioritized as the prevailing solutions to social and public health issues. As new courts are created, the process of referring people to them is increasingly normalized, even though the evidence strongly suggests that specialty courts simply do not improve public safety, public health, or quality of life. Participation tends to involve at least some jail time, and so many participants are unable to complete them that they only just barely qualify as a form of diversion. No matter what specialty courts are called, they are still courts, entrenched in the punitive criminal legal system and accompanied by the many harms of arrest, conviction, and incarceration.

Footnotes

-

Specialty courts are not literally entirely separate entities from traditional criminal courts; rather, they are an alternative docket (a log of upcoming cases) within the court system overseen by a specialty court judge and associated personnel. ↩

-

Connecticut had two or three drug courts in the past few years, but the state did not have any operating specialty courts as of the end of 2024, according to the National Treatment Courts Resource Center. ↩

-

For example, Oklahoma County’s Treatment Court program purports to have avoided 12,243 years of incarceration, based on the average sentence of seven years (though it’s unclear how they arrived at these figures), leading to a savings of over $219 million for county taxpayers. This is based on the difference between the cost of incarceration and the operating cost of their Drug Court. ↩

-

Most discussions of the criminal legal system treat adults and youth courts separately, but the National Treatment Court Resource Center includes both types in their census. When including juvenile drug courts, just over 50% of specialty courts are drug courts. ↩

-

Other documented but less common specialty courts include community courts, reentry courts (for people leaving incarceration), homeless courts, and courts for sexually exploited people. ↩

-

Tribal courts operate “Tribal Healing to Wellness” courts, which are drug courts adapted to individual tribal communities. ↩

-

AllRise, a national organization promoting specialty courts, found that “150,000-plus” individuals are served by these courts annually, but it’s unclear how this figure was calculated. This estimate seems to agree with the National Treatment Court Resource Center’s participation data (see Table 1), which totaled just over 120,000 enrollments in the major treatment court categories, but did not include participation in specialty court types such as reentry courts and non-drug juvenile courts. ↩

-

The number of specialty courts in a state does not necessarily correspond to how many people participate. Some states have far more courts than others, but state- and court- level participation data are often unavailable, so data on the number of courts should not be taken to represent the size of their impact. For example, Arizona had five drug courts as of 2023 serving about 1,500 people annually; meanwhile, Maine had eight drug courts in 2024, but served fewer than one-fourth as many people. ↩

-

As many experts have pointed out, many studies on specialty courts suffer from methodological flaws that call their outcomes into question. The biggest issue plaguing these studies is the comparison of participants and non-participants, whose inherent differences (such as their criminal charges) can lead to selection bias and throw off the validity of results. ↩

-

In this case, jail time could include pre- and post-disposition incarceration, as well as any time served due to probation violations, if the probation stemmed from the initial arrest. ↩

-

According to the report’s authors, this difference in arrest activity may be due to law enforcement actively working to bring opioid intervention court participants with warrants in front of a judge. This clear case of “net-widening” is another problem with specialty courts, which appears later in this briefing. ↩

-

If having any criminal record is a means for disqualification, then an estimated 79 million people or more nationwide stand to be excluded from specialty court programs. ↩

-

According to our own analysis of jail data, 38% of people in a sample of jails had a violent “top charge” and 4.9% had a weapons offense as one of their charges. This amounts to almost 108,000 people potentially excluded on a single day, to say nothing of the massive turnover in jails. As for people facing a drug trafficking charge, which is often a federal crime, US Sentencing Commission data suggest that about 18,000 federal cases involved drug trafficking in 2024. ↩

-

In some cases, even the victim must consent to someone’s participation; fortunately, national survey data indicate that crime victims prefer treatment and rehabilitation, such as through a specialty court, to incarceration. ↩

-

It’s not possible to pin down exactly what percentage of specialty courts dealing with substance use disorders require abstinence for program advancement or graduation, but it is certainly the rule rather than the exception. For example, most specialty courts in Cook County, Ill. used abstinence-only models; information about Idaho’s drug courts suggests that abstinence is required from the very first phase of programming. ↩

-

According to one critique of drug courts, the motivation for increased arrests is that police and prosecutors believe “something worthwhile… can happen to offenders once they are in the system.” ↩

-

According to the survey, some specialty courts using jail sanctions for positive drug tests reported that they did so regardless of a participant’s “clinical stability” — meaning 90 or more drug-free days, as measured by drug tests. This distinction built into the survey’s question may suggest that jailing someone who has been reliably drug-free for a period of time would not disrupt their treatment, but there is no guarantee of such resiliency. ↩

-

As one example of removing jail as a possible consequence during court-supervised treatment, California’s probation-supervised treatment program, a now-defunct initiative, did not allow incarceration as a sanction; its completion rates were similar to those of traditional drug courts. ↩

-

Some would argue that the nature of specialty courts actually requires some partiality from judges and other stakeholders, given a shared goal (the participant’s recovery). But while this bias may seem like it could only favor a participant — in that getting to know someone might sway a judge toward lesser sanctions or second chances — experts have pointed out that judicial bias may have the opposite effect. ↩

-

In a 2021 law review article, law professor Erin R. Collins argues that because judges like specialty courts, and because national professional associations such as the Conference of State Court Administrators herald them (specifically drug courts) as the “most effective” intervention available for drug abuse and crime, these courts will continue to proliferate and will resist changes to their structure and function. ↩

-

However, one of the federal agencies which oversees grants that fund problem-solving courts — SAMHSA, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — has been gutted by the Trump administration, jeopardizing the future of these courts. Some of the SAMHSA layoffs are in limbo due while courts decide whether or not they were legal dismissals, but the agency is a fraction of the size it once was. ↩

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.