- This topic is empty.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 29, 2025 at 3:14 am #10903

Kris Marker

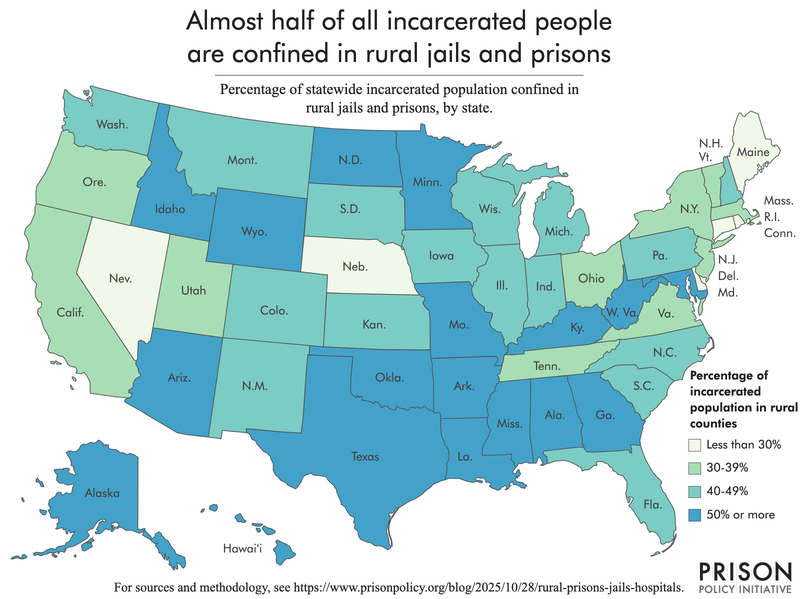

KeymasterNearly a million incarcerated people depend on rural hospitals for routine off-site and emergency medical care.1 Almost 60% of people in prisons and 25% of those in local jails are confined in rural counties, which are home to 3,000 of the nation’s correctional facilities. Following massive cuts to Medicaid passed by Congress this year, many rural hospitals will be forced to scale back operations or close entirely. As a result, critical, lifesaving healthcare will be further out of reach for huge swaths of the incarcerated population and those who live and work nearby, making an already bad situation far, far worse.

The divisive “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” imposes significant cuts to Medicaid that slash funding for rural hospitals,2 which are largely dependent on federal subsidies to stay afloat.3 Closing rural hospitals has disastrous consequences for entire communities, but especially for incarcerated people who have no choice about where they receive medical care. Rural communities can expect limited access to emergency care, higher costs for healthcare, and less-timely and more geographically distant medical treatment. The resulting loss of jobs and healthcare providers risks escalating poverty, unemployment, and disability rates, exacerbating an already dangerous cycle that often leads to incarceration.

In this briefing, we present our estimates of the number of people in prisons and jails who are locked up in rural counties and explain how rural hospital closures would spike healthcare and incarceration costs while worsening public health. We are also making these state-by-state estimates available in an appendix. Additionally, we examine how a weakened rural hospital system can make healthcare delivery even worse than it already is for people on the inside. Finally, we highlight ways in which the consequences of rural hospital closures — unemployment, inadequate healthcare access, poverty — are felt across entire rural communities, not just behind bars.

The incarcerated population is disproportionately sick, aging, and locked up in rural areas

With more than half of prisons and around a quarter of local jails situated in rural counties, rural hospital closures pose real risks to incarcerated people’s health and wellbeing.4 Incarceration has a negative impact on the health of people behind bars and shortens life expectancies — a state of affairs that is especially worrisome given the increasingly elderly and sick incarcerated population.5 Researchers warn that closing rural hospitals “can increase the risk of bad outcomes for conditions requiring urgent care, including that for high-risk deliveries, trauma, and heart conditions.” These bad outcomes are particularly likely among the incarcerated population, where some of these conditions are common: for example, about 2% of women entering jail are pregnant and many jail births are high risk. Additionally, heart conditions are the second leading cause of death in prisons and jails. Many correctional facilities already struggle to provide basic healthcare to incarcerated people and have disturbingly high mortality rates. These issues will inevitably worsen with the loss of important medical infrastructure nearby.

The impact on state prison systems

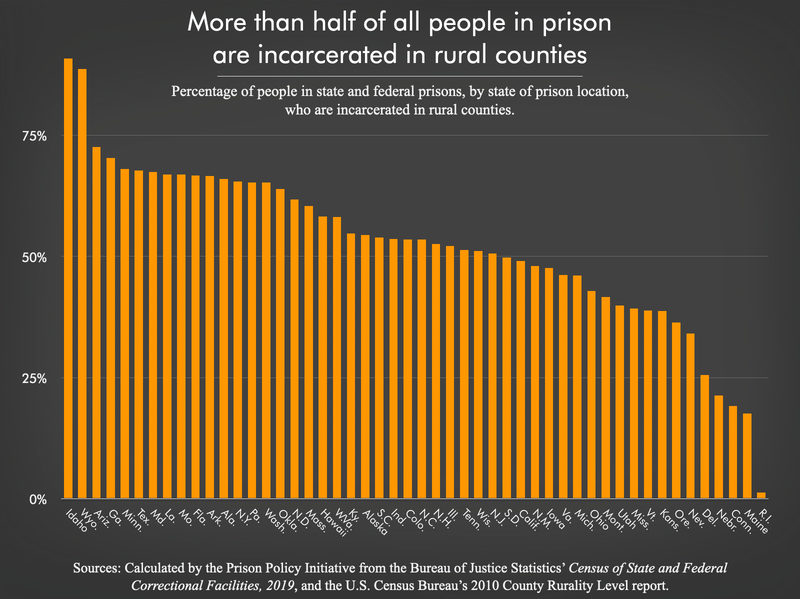

In almost every state, thousands of people in prison who need emergency and routine off-site medical care (such as imaging and x-rays, surgeries, and specialist care) rely on nearby rural healthcare systems that are now threatened by Medicaid cuts. This is particularly alarming in states that almost exclusively hold incarcerated people in rural areas, like Idaho, where 91% of people in prison are in rural counties.6 But the scale of the problem is worse in states with some of the largest prison systems — like Texas, Florida, California, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and New York — where between 30,000 and 117,000 people in rural prisons rely on those hospitals in each state. Nationally, more than 783,000 people are in prisons in rural counties.7

People in prison already have to contend with delayed referrals to medical specialists, which (along with understaffing) contribute to higher mortality (death) rates on the inside. The carceral system is notorious for denying and slow-walking medical care, and for the convoluted, lengthy process required to be seen by a healthcare provider — practices that undoubtedly contribute to higher mortality rates on the inside.8 In rural facilities, these conditions are often exceptionally bad.

In Louisiana — where 42% of the state prison population is incarcerated in rural counties — the prison mortality rate is more than double the national rate in state prisons, according to the most recent national data. From 2001-2019, Louisiana had the highest prison mortality rate overall, as well as for deaths related to heart disease, cancer, AIDS-related illnesses, and respiratory disease. Such severe healthcare needs require ready access to emergency and specialist care at a nearby hospital, and yet the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform estimates that 46% of Louisiana’s rural hospitals are at risk of closure, with at least nine at immediate risk of closure due to federal funding cuts.

Impact on local jails

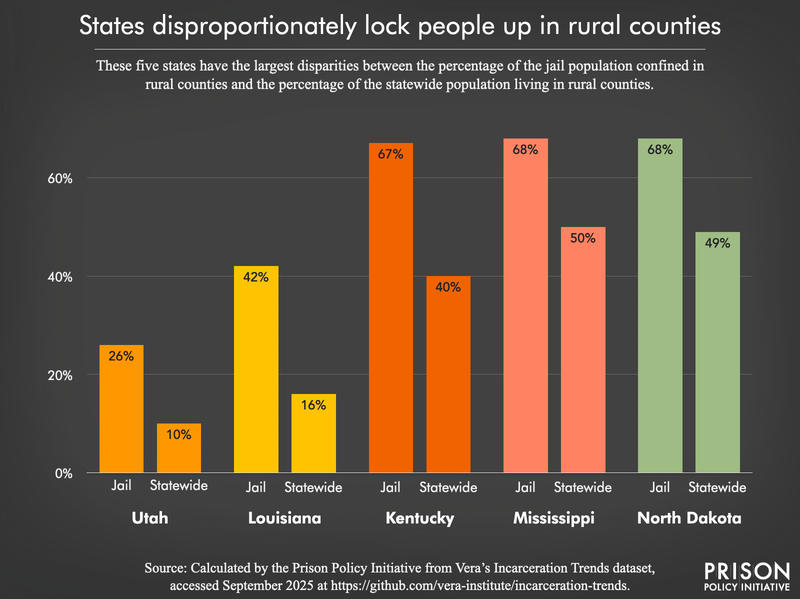

Nationally, almost 170,000 people are incarcerated in rural jails. In 19 states, more than one-third of the statewide jail population is confined in rural counties. Six of those states confine more than half of their entire jail population in rural counties.9 Even in states with large rural populations overall, the share of the jail population in rural counties still stands out: for example, in Mississippi, where about half of the statewide population lives in rural areas, almost 70% of people in jail are held in rural counties. In Kentucky, where around 40% of the state lives outside of metropolitan areas, a disproportionate 67% of the statewide jail population is confined in rural jails.

Each year, more than five million people are arrested and booked into jail and they are more likely to have serious health needs — including mental illness, substance use disorders, HIV, Hepatitis B or C, cirrhosis, and heart conditions — than people who are not jailed. Troublingly, small, predominantly rural jails consistently report the highest jail mortality (death) rates in the country.10

The medical care that people receive inside jails is terrible in most places, but it is particularly bad in states with mostly rural jails and prisons. These facilities compete with community healthcare systems for limited resources, including qualified staff, and their failure to provide adequate medical care on the inside puts additional strain on local hospitals. When patients arrive from the jail or prison, their care has often already been delayed, making their health issues more severe and likely to require emergency or specialized treatment.

For example, in Virginia, where about 40% of the state’s prison and jail facilities are in rural areas, there have been at least three civil rights cases related to healthcare in prisons and jails since 2010. In U.S. vs. Piedmont Regional Jail Authority (2013), the U.S. Department of Justice alleged that the rural regional jail in Prince Edward County was permitting unqualified staff to evaluate medical conditions, inadequately screening for medical issues on admission, and providing subpar mental healthcare. The lawsuit resulted in the appointment of a court monitor to oversee the jail’s efforts to address these issues, but subsequent jail deaths suggest problems persisted. Similarly, in West Virginia — where 53% of the jail population is in rural counties — formerly incarcerated people already report serious healthcare issues on the inside, including delays in cancer screenings, lack of access to insulin, and abrupt discontinuation of prescription medication. Accordingly, West Virginia also had the second highest jail mortality rate in the nation at last count in 2019.

Rural hospital closures are associated with rising healthcare and incarceration costs, and worse public health outcomes

In the past decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed and more are at risk: the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform reports that in most states, over 25% of rural hospitals are at risk of closing, and in 10 states, at least half are at risk as of August 2025. Aside from providing crucial emergency care, inpatient medical care, and laboratory testing and diagnostics, rural hospitals are often where the community receives routine primary care and inpatient rehabilitation services. These closures can “wreak irreparable havoc on rural communities” and will, in turn, make it harder to reverse local population declines, threatening to turn these communities into “ghost towns.”

Beyond the community-wide effects of hospital closures – including unemployment (including in non-healthcare industries), lower income levels, and slower economic growth – the tendency of police to target poor and chronically ill populations means that people who fall through the cracks as a result of these cuts to crucial federal subsidies risk being swept into the system. With evidence that high county jail incarceration rates are associated with a rise in county-wide deaths, Medicaid cuts risk accelerating a dangerous cycle of poverty, illness, incarceration, and death in rural communities.

Medicaid cuts also stand to make already-costly medical care for incarcerated people far more expensive by placing services further out of reach. People living in rural areas live an average of 10.5 miles from the nearest hospital (roughly twice the distance in other areas), and over one-third of rural hospitals that closed between 2013 and 2017 were more than 20 miles from the nearest hospital. States, counties, and municipalities are ultimately on the hook for the high and steadily rising costs associated with medical care for incarcerated people. In Cheshire County, New Hampshire, for example, the county jail already budgets $50,000 for healthcare outside of the facility, which is expected to cover medical care for 100 people in jail, including one person who requires dialysis to the tune of $6,000 every month. In Virginia, 27% of the prison healthcare budget in 2015 was spent on off-site hospital care.

In particular, the costs of transporting incarcerated people to hospitals for off-site or emergency care are already extreme. In Michigan, the cost for 224 ambulance trips to the rural Chippewa County Correctional Facility is upwards of $430,000.11 Meanwhile, in New Hampshire, Department of Corrections expenditures on ambulances rose by 176% from 2022 to 2023. Requiring transport to hospitals that are further away will cause these costs to climb even higher, and will incentivize corrections departments to avoid doing so as much as possible.12 Prisons and jails already engage in this practice because of untenably high transport and staffing expenses.13 In Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, (which is not even a rural county), medical transport from the jail “takes two correctional officers out of the jail for up to 10 hours.” In a survey of jail staff in southeastern states, one jail employee reported that they “try and get rid of dialysis patients as quickly as [they] can, too, because they don’t wanna have to transport them three days a week to dialysis.” In addition to delaying offsite transportation as much as possible, corrections authorities may also try to deflect rising costs onto their (typically poor) incarcerated patients. As the National Consumer Law Center notes, jails in at least 25 states already engage in such practices:

“When an incarcerated person suffers from an acute medical issue that requires care that the jail cannot provide in-house, some sheriffs will release the person on “medical bond” before transporting them to a hospital so that the jail will not have to pay the medical bills. Once the person receives treatment and recovers, the sheriffs then often quickly move to rearrest and book the person back into jail.”

The failure to address people’s health needs while incarcerated exerts pressure on the remaining healthcare infrastructure as sick people leave correctional facilities and return home. For example, people on probation and parole face higher rates of substance use disorders, mental health diagnoses, chronic conditions, and disabilities than the general population, and over a quarter of people on community supervision have no health insurance, further limiting their access to adequate healthcare in the community.

Conclusion

The latest cuts to Medicaid pose substantial risks to both rural communities and the people who are incarcerated within them. Healthcare for incarcerated people is already abysmal, and jails and prison systems have been complaining about the rising medical costs for years. Medicaid cuts will pour fuel on this fire by forcing many rural hospitals to close. Further restricting timely access to routine off-site and emergency medical care will stoke worse health outcomes and higher mortality rates for an aging confined population. Given that most incarcerated people will eventually return to the community, these problems will exacerbate larger public health issues, impact community-wide mortality, and further burden the existing, limited emergency medical services in rural communities. Taken together, these factors paint a grim picture of the future for all people in rural communities as the combination of poor health and poverty makes rural communities more of a target for policing and incarceration. The destruction of rural public health infrastructure is a policy choice that inevitably favors using jails and prisons to manage increasingly poor, sick, and neglected populations through punishment rather than care.

Methodology

To estimate the number of incarcerated people who are locked up in rural communities at risk for hospital closures, we used a number of sources, including the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019 and Vera’s Incarceration Trends dataset. Because our focus in this analysis is on the ratio of people confined in rural areas to those confined in non-rural areas, we did not adjust the custody populations reported in either the prison data (Bureau of Justice Statistics) or the jail data (Vera) to account for the number of people who are held in local jails but are under state or federal jurisdictional authority, as we do in analyses focused on confinement by different government agencies.14 Additionally, the data from these sources are from different years (i.e., 2019 for prisons and between 2019 and 2024 for jails). For these reasons, we recommend caution when repurposing the prison and jail populations included in this briefing.

- Prisons: To estimate the number of people in state and federal prisons located in rural counties, we used the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019.15 While the number of people confined in the facilities included in this Census has changed since 2019, we are focused on the ratio of people incarcerated in rural facilities to those in non-rural facilities, and we assumed this ratio has remained relatively consistent since 2019. Each facility included in the Census provides a facility address with a street number, city, state, and ZIP code.16 From the provided ZIP code, we used the HUD-USPS ZIP Code Crosswalk files published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to identify the county that each facility is located in. We then used the 2010 County Rurality Level published by the U.S. Census Bureau to identify which counties with state and federal correctional facilities are classified as rural. The County Rurality Level distinguishes counties by the percentage of the county population living in rural areas:

- Mostly urban: Less than 50% of the county population lives in rural areas;

- Mostly rural: 50-99.9% of the county population lives in rural areas; and,

- Completely rural: 100% of the county population lives in rural areas.

After identifying the rurality of the counties housing each facility in the Census, we created statewide estimates for the number of state and federal facilities located in mostly or completely rural counties. In the Census, each facility reports the number of people it held on June 30, 2019 (variable V074 – “inmate total”), and we used these populations to calculate the estimated number of people incarcerated in state and federal facilities located in mostly or completely rural counties.

Using this methodology, we found that there were 932 state and federal correctional facilities in the Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019, located in mostly or completely rural counties (55% of all facilities in the survey). Nationally, we found that around 58% of people in state and federal correctional facilities in 2019 were incarcerated in mostly or completely rural counties. - Jails: To estimate the number of people in local jails located in rural areas, we relied primarily on Vera’s Incarceration Trends dataset for all states except West Virginia and Virginia (see below for details on the methodology used for these states). We did not analyze jail data for the six states with combined prison and jail systems (Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont). We used the most recent jail populations available in the Vera dataset for each jurisdiction: for over 1,200 jail jurisdictions, the most recent jail populations were reported for the first quarter of 2024 and for the remaining jurisdictions, we relied on the 2019 second quarter data (which originates from the Bureau of Justice Statistics Census of Jails, 2019).

Because West Virginia and Virginia operate regional jail systems,17 we did not use the statewide jail population as reported in Vera’s Incarceration Trends dataset, but instead compiled our own jail populations and identified the counties containing the facilities. To estimate the number of people confined in jails in rural counties in West Virginia, we used the average daily population for FY 2024 for the regional jails as reported in the West Virginia Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s Annual Report (this report also lists the county that each regional jail facility is located in). For Virginia, we used the March 2024 average daily population for each of Virginia’s jails as reported by the state Compensation Board’s Local Inmate Data System. We then researched each facility’s physical address to identify the county or independent city that each facility is located in.18 Once we identified the counties containing the West Virginia and Virginia jail facilities, we matched these counties with the Vera Incarceration Trend’s dataset to identify which of these counties are rural.

Vera’s dataset assigns a level of “urbanicity” to each jurisdiction based on the 2023 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. We relied on this classification scheme for all jail jurisdictions to identify which were considered rural. Ultimately, we included jail populations for more than 2,700 jurisdictions in our analysis, with about 62% of jails identified as rural.

- Rural state and county populations: In this briefing, we compare the percentage of people incarcerated in rural communities to the number of people statewide who live in rural communities. To calculate these estimates, we relied primarily on the county populations included in the Vera datasets. For the two states we collected data outside of Vera’s Incarceration Trends, we used the percentage of people living in rural counties in 2023 as reported in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s State Fact Sheets for Virginia and West Virginia.

Read the entire methodology

Footnotes

-

State governments rely on hospitals to provide off-site care for people in prison. Similarly, local jails have limited resources to provide healthcare inside and depend on local hospitals and ambulance services for emergency care, diagnostics, and specialty clinics. While all correctional facilities inevitably face the challenges of providing healthcare to an aging and ailing incarcerated population, rural jails are “further disadvantaged by their location,” often with fewer financial resources and limited access to nearby healthcare institutions. ↩

-

Though the law included a $50 billion rural hospital grants program, it seems unlikely to soften the blow Medicaid cuts will deliver to these critical safety net facilities. Analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the pool of grant money is less than would be needed to cover the shortfall, the grants are timed for before the cuts go into effect, and it’s unclear if the funds will be directed to the rural hospitals that need them the most. ↩

-

Medicaid and Medicare accounted for 44% of the $1.5 trillion spent on hospital care in 2023 and provide additional funding for the vast majority (96%) of rural hospitals through special payment designations, like critical access hospitals, rural emergency hospitals, and sole community hospitals. Reducing federal payments to hospitals — particularly vulnerable rural and safety-net hospitals — will likely shift the costs of healthcare onto patients and result in hospitals providing fewer services, limiting access to necessary care. Importantly, people do not “collect Medicaid benefits,” as some proponents of Medicaid cuts have misleadingly argued; instead, Medicaid payments are made to hospitals, clinics, and medical providers. ↩

-

In the “prison building boom” from 1970 to 2010, nearly 70% of new prisons were built in rural areas. Many communities suffering from unemployment and deindustrialization were sold the idea that prisons could help turn things around, but the reality is that prisons actually deepen poverty in these (mostly rural) communities, and cuts to hospital infrastructure will aggravate these conditions. ↩

-

People in prison experience a number of chronic health conditions and infectious diseases at higher rates than the general public, including asthma, substance use disorders, Hepatitis B and C, and HIV. While people are in prison, however, access to healthcare is not necessarily a given: nearly 1 in 5 (19%) people in state prison have gone without a single health-related visit since entering prison. ↩

-

Similarly, the vast majority of people in prison in Wyoming (89%), Arizona (73%), Georgia (70%), Minnesota (68%), Texas (68%), and Maryland (67%) are in facilities in rural counties. See the appendix table for more details.

↩ -

This estimate is based on data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, 2019, which is the most recent national data collection with facility populations and facility addresses, allowing us to identify how many people are incarcerated in rural facilities. However, we know that prison populations have declined about 12% nationally since 2019, and therefore encourage readers to use caution with this estimate. To see details on state-by-state population changes, see the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Prisoners in 2023. ↩

-

Researchers found that among the 5,000 people who died in federal prisons in the last decade, “more than a dozen waited months or even years for treatment, including inmates with obviously concerning symptoms: unexplained bleeding, a suspicious lump, intense pain.” In a federal prison in Oregon, a U.S. Department of Justice inspection found widespread lack of medical services, an extensive backlog of diagnostic tests (which prevented the facility’s physician from monitoring the health of patients with diabetes and Hepatitis C), and severe understaffing in medical positions. ↩

-

Those six states are West Virginia, Montana, Wyoming, Kentucky, Mississippi, and North Dakota. See the appendix table for more details. ↩

-

In Kentucky, more than 3 in every 5 incarcerated people in the state (62%) are confined in rural jails and prisons. Based on our own analysis of the Lexington Herald-Leader’s jail death data and using the rural classification system included Vera’s jail Incarceration Trends data (for details on the rural classification scheme, see the methodology), between 2020 and 2024, 234 people died in Kentucky jails, at least 58% of whom were jailed in rural counties. In 2024 alone, rural counties were home to 64% of Kentucky’s jail deaths. ↩

-

Although not all ambulance calls to the jail result in a subsequent trip to the hospital, it is worth noting that the nearest hospital is a rural hospital, MyMichgan Medical Center-Sault, located about 20 miles away from the jail. The ambulance/emergency services company in Michigan is waiting for Wellpath (the private healthcare contractor for Chippewa County Correctional Facility) to pay the $434,000 bill. In November 2024, Wellpath filed for bankruptcy. ↩

-

Jails and prisons have also turned to telehealth resources as a means to control healthcare spending, including telehealth assessment and linkage to medications for opioid use disorder. In 2011, at least 30 states reported using telemedicine in prisons for at least one type of specialty or diagnostic service, like psychiatry and cardiology. In the face of rural hospital closures, telehealth often makes sense as a tool to improve access to medical care and lower transportation costs, but it cannot — and should not be expected to — replace the infrastructure and services provided by rural hospitals and emergency rooms. ↩

-

In a survey of jail staff in southeastern states, researchers found that there was some financial incentive to not transport people to the hospital because, in some cases, “a jail was billed if [the ambulance] transported the individual, but was not billed if [ambulance personnel] only conducted an on-site assessment without transporting the individual.” When sick people are eventually transported offsite for medical care, the journey can be dangerous and often require spending hours shackled to other people in a prison van with no air conditioning or bathroom breaks. Some treatments and procedures require frequent return trips to the hospital, which will be complicated by increased distance to the nearest hospital. ↩

-

For state-specific data on the number of people held in local jails for other authorities (including state and federal authorities), see New data and visualizations spotlight states’ reliance on excessive jailing. ↩

-

The 2019 Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities is the most recent national census of prison facilities from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. ↩

-

There is some room for error here: the survey requests the physical addresses of the facilities, but we know that it is possible some facilities reported a mailing address, an office address, or some other address that does not accurately represent the location of the physical facility where people are incarcerated. ↩

-

Most local jails are run by counties or cities, but there are also “regional” jails, which the Bureau of Justice Statistics explains are “created by two or more local governing bodies through cooperative agreements.” West Virginia’s jail system is entirely composed of regional jails and there are a number of regional jails in Virginia. Other states — including (but not limited to) Ohio, North Dakota, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Kentucky — have regional jails, but these make up a much smaller portion of these states’ jail systems, so we relied on the county-level data reported by Vera for all other states. ↩

-

Virginia has 95 counties and 38 county-equivalent cities. These 38 independent cities are considered “county-equivalents” for Census purposes because they have the same level of government as counties. ↩

See all footnotes

Appendix Table 1: State and federal correctional facility populations, by state and county rurality, 2019

This table does not include Washington, D.C.. State Percentage of prison population in rural counties Estimated number of people in prison in rural counties Total prison population Number of state or federal correctional facilities in rural counties Total number of state and federal correctional facilities Alaska 54% 2,570 4,720 13 19 Alabama 66% 16,019 24,276 17 33 Arkansas 67% 12,489 18,759 13 23 Arizona 73% 35,010 48,242 18 28 California 49% 68,734 140,120 34 71 Colorado 54% 12,491 23,338 20 42 Connecticut 19% 2,889 15,115 10 41 Delaware 26% 1,328 5,197 3 11 Florida 67% 70,613 105,878 118 159 Georgia 70% 40,745 57,930 47 68 Hawaii 58% 2,376 4,076 6 10 Iowa 48% 4,856 10,192 19 34 Idaho 91% 6,924 7,619 13 15 Illinois 52% 22,993 44,044 20 40 Indiana 54% 15,433 28,811 13 24 Kansas 39% 4,564 11,766 8 14 Kentucky 55% 11,451 20,917 22 42 Louisiana 67% 15,361 22,944 16 19 Massachusetts 60% 5,706 9,450 11 18 Maryland 67% 13,255 19,643 10 21 Maine 18% 396 2,252 1 6 Michigan 46% 18,528 40,239 16 37 Minnesota 68% 8,420 12,380 10 18 Missouri 67% 20,075 30,015 25 38 Mississippi 39% 7,325 18,643 10 22 Montana 42% 1,519 3,645 12 20 North Carolina 53% 21,774 40,724 32 65 North Dakota 62% 1,115 1,804 5 10 Nebraska 21% 1,183 5,550 3 12 New Hampshire 53% 1,739 3,305 5 9 New Jersey 51% 12,480 24,669 13 31 New Mexico 48% 3,081 6,413 5 17 Nevada 34% 4,406 12,935 7 19 New York 65% 30,596 46,756 36 59 Ohio 43% 22,725 52,949 32 59 Oklahoma 64% 19,696 30,792 24 35 Oregon 36% 6,028 16,582 8 20 Pennsylvania 65% 38,178 58,487 31 62 Rhode Island 1% 35 2,698 1 7 South Carolina 54% 13,452 24,946 13 29 South Dakota 50% 2,018 4,054 6 9 Tennessee 51% 12,054 23,496 10 22 Texas 68% 116,764 172,364 94 158 Utah 40% 2,279 5,722 7 8 Virginia 46% 16,152 34,984 23 51 Vermont 39% 579 1,489 3 6 Washington 65% 11,350 17,393 16 28 Wisconsin 51% 12,672 24,786 26 52 West Virginia 58% 8,765 15,067 18 26 Wyoming 89% 1,965 2,215 7 8 Total 58% 783,156 1,360,391 930 1,675 Sources and methodology

- Percentage of prison population in rural counties

- Percentage of the statewide population of people in state and federal correctional facilities who are in facilities in mostly or completely rural counties. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019 and the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 County Rurality Level report.

- Estimated number of people in prison in rural counties

- Estimated number of the statewide population of people in state and federal correctional facilities who are in facilities in mostly or completely counties. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019 and the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 County Rurality Level report.

- Total prison population

- Number of people in state and federal correctional facilities, by state, as reported in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019.

- Number of state or federal correctional facilities in rural counties

- Number of state and federal correctional facilities, by state, in mostly or completely rural counties. Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019 and the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 County Rurality Level report.

- Total number of state and federal correctional facilities

- Number of state and federal correctional facilities, by state, as reported in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019.

Appendix Table 2: Local jail populations, by state and county rurality, 2024

This table does not include Washington, D.C. or the six states with combined prison and jail systems (Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont). State Percentage of statewide jail population in rural counties Estimated number of people in local jails in rural counties Total statewide jail population Percentage of total statewide population living in rural counties Alabama 25% 4,087 16,063 23% Arkansas 38% 3,566 9,405 35% Arizona 8% 992 12,363 5% California 3% 1,884 59,273 2% Colorado 16% 1,783 10,902 12% Florida 6% 3,267 53,203 3% Georgia 23% 9,791 43,055 17% Iowa 39% 1,999 5,076 40% Idaho 35% 1,477 4,194 32% Illinois 19% 2,782 14,865 11% Indiana 29% 5,382 18,628 21% Kansas 43% 3,020 7,064 30% Kentucky 67% 19,338 29,018 40% Louisiana 42% 14,058 33,148 16% Massachusetts 5% 351 7,092 2% Maryland 4% 279 7,371 2% Maine 40% 710 1,756 34% Michigan 27% 4,094 15,110 18% Minnesota 35% 2,433 6,972 22% Missouri 34% 4,166 12,324 21% Mississippi 68% 9,209 13,610 50% Montana 58% 1,812 3,143 64% North Carolina 29% 5,761 19,557 20% North Dakota 68% 1,543 2,258 49% Nebraska 36% 1,430 3,982 31% New Hampshire 42% 633 1,524 37% New Jersey 0% 0 9,050 0% New Mexico 42% 2,715 6,530 33% Nevada 12% 718 5,984 8% New York 4% 1,761 41,059 7% Ohio 30% 6,994 23,356 20% Oklahoma 45% 4,680 10,329 33% Oregon 28% 1,745 6,218 16% Pennsylvania 11% 3,349 29,150 11% South Carolina 20% 2,422 11,891 15% South Dakota 37% 1,002 2,705 42% Tennessee 28% 7,627 26,788 22% Texas 22% 16,024 71,839 10% Utah 26% 1,769 6,910 10% Virginia 18% 3,638 20,782 12% Washington 12% 1,280 10,252 9% Wisconsin 32% 3,285 10,224 26% West Virginia 53% 2,570 4,811 39% Wyoming 61% 886 1,450 64% Total 24% 168,312 712,141 14% Sources and methodology

- Percentage of statewide jail population in rural counties

- The estimated percentage of the statewide jail population who are in jails in rural counties. Sources: Vera’s Incarceration Trends populations from Q1 2024 when available, or Q2 2019 when 2024 data was not available. As explained in the methodology, data for West Virginia are from the Department of Corrections’ FY 2024 Annual Report and the data for Virginia are from the state Compensation Board’s Local Inmate Data System for March 2024.

- Estimated number of people in local jails in rural counties

- The estimated number of people in jails in rural counties. Sources: Vera’s Incarceration Trends populations from Q1 2024 when available, or Q2 2019 when 2024 data was not available. As explained in the methodology, data for West Virginia are from the Department of Corrections’ FY 2024 Annual Report and the data for Virginia are from the state Compensation Board’s Local Inmate Data System for March 2024.

- Total statewide jail population

- The estimated number of people in jails in each state. Sources: Vera’s Incarceration Trends populations from Q1 2024 when available, or Q2 2019 when 2024 data was not available. As explained in the methodology, data for West Virginia are from the Department of Corrections’ FY 2024 Annual Report and the data for Virginia are from the state Compensation Board’s Local Inmate Data System for March 2024.

- Percentage of total statewide population living in rural counties

- The percentage of the statewide population living in rural counties. Sources: Vera’s Incarceration Trends populations from Q1 2024 when available, or Q2 2019 when 2024 data was not available. As explained in the methodology, data for West Virginia and Virginia are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2023 fact sheets.

- Prisons: To estimate the number of people in state and federal prisons located in rural counties, we used the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2019.15 While the number of people confined in the facilities included in this Census has changed since 2019, we are focused on the ratio of people incarcerated in rural facilities to those in non-rural facilities, and we assumed this ratio has remained relatively consistent since 2019. Each facility included in the Census provides a facility address with a street number, city, state, and ZIP code.16 From the provided ZIP code, we used the HUD-USPS ZIP Code Crosswalk files published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to identify the county that each facility is located in. We then used the 2010 County Rurality Level published by the U.S. Census Bureau to identify which counties with state and federal correctional facilities are classified as rural. The County Rurality Level distinguishes counties by the percentage of the county population living in rural areas:

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.